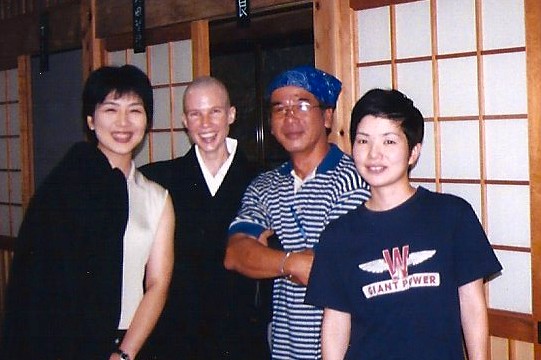

Gretel Ehrlich and her translator visited Reiko-san this past week. I have only this photo so far. I can’t wait to hear all about it when Gretel returns to the States.

Stories, Impressions, & Photos from June in Northern Japan

Here’s an update on Dai-En Bennage Roshi, who has been volunteering in Northern Japan:

Dear Sangha,

I just spoke with NiOsho (Dai-En Bennage Roshi) over the phone. Here is the update:

After departing from Koen Hunter and Nanshin White in Kyoto, NiOsho went to visit Fukan-san in Miyagi prefecture. Fukan lives just on the edge of where the tsunami hit. Dai-En spent three days with Fukan and Fukan’s family and was able to see first-hand the devastation from the tsunami. At one Pure Land Sect temple the gravestone markers were flung around as though styrofoam. There is a lot of debris everywhere.

Fukan’s family was very warm and welcoming to Dai-En prior to her departure for Morioka City to see her friend, Teiko Abe-san. Abe-san led Dai-En to Kannonji, Yamamoto Tessai Roshi’s (the Dharma brother of Maura Soshin O’Hallaran and teacher of Rev. Tenku Ruff) temple. There she was given permission to use Yamamoto Roshi’s car. With Abe-san as her guide, she drove to the volunteer center on October 14th.

Dai-En has been riding in a caravan full of volunteers about a 2 hours’ distance to some of the worst hit regions of the tsunami. Unfortunately, she is not allowed to take photos. All along the highways on the way to the site she can see debris, damage, and construction vehicles. At the volunteer center she was taught a method of “tapping touch,” a kind of gentle massage, to use on the earthquake victims to help them with the trauma of the earthquake. After doing “tapping touch,” Dai-En listens to the survivors’ stories. She was also able to give a Dharma Talk to the people she was ministering to, which was very well received. One older man commented that he could not believe he was hearing words of the Dharma coming out of a foreign woman.

Everyone returns in the caravan for the 2 hour distance drive back to the volunteer center. At the volunteer center wake up time is 6:30. Bed time is 10pm. There are volunteers from all over the world staying with her at the center. Basically, they have a microwave with which to cook their food. Volunteers are expected to bring their own food or to go out for meals. Dai-En was given a lot of wholesome foods by Abe-san plus a futon on which to sleep. There is also a public bath about 2 miles away from the center which she makes certain to go to every other day.

Dai-En sounds quite well. She stayed at the volunteer center until the 29th of October, then returned to Abe-san’s home for the weekend before heading to the NiSodo (women’s monastery) in Nagoya for sesshin (silent retreat). She plans to visit some of the older nuns she practiced with many years ago before returning to the States on the 12th of November.

Below are some photos of Dai-En with Koen and Nanshin, and Choro in Kyoto.

Gassho,

Daishin

(Dai-En’s disciple at Mt. Equity Zendo)

Last week Dai-En Bennage Roshi the Abbess of Mt. Equity Zendo in Pennsylvania left for Japan. She will spend a good part of her trip volunteering in the tsunami-hit regions of Northern Japan. I am happy Bennage Roshi will be going to Northern Japan for many reasons. First, she trained in Japanese monasteries for 12 years and is fluent in Japanese. She will be able to use her training to help the survivors who are still very much suffering. Second, Bennage Roshi trained with my teacher many years ago at Hokyoji Monastery and he admires her greatly. Finally, Bennage Roshi was partially responsible for getting the memoirs of Maura Soshin O’Halloran published . She had heard of Soshin through my teacher, who was Soshin’s Dharma brother, during the time they trained together at Hokyoji. Later, she was able to connect with Soshin’s mother and to aid her in getting the manuscript to a publisher. Bennage Roshi will be using Kannonji, the temple where Soshin practiced, as a home base for her volunteer work. I’m very much looking forward to sharing stories from Bennage Roshi’s trip on this blog. In the mean time, here are a few photos.

This story was in the Mainichi Daily News today. It’s about the mother I mentioned in The Saddest Day post who got a heavy machinery license to search for her daughter’s missing body. Her daughter was finally found several miles from Okawa Elementary School.

Mother determined to keep up search for missing children after daughter found dead

Naomi Hiratsuka, pictured here on Sept. 6, acquired a license to operate heavy machinery to search for children missing from the March 11 tsunami. (Mainichi)

ISHINOMAKI, Miyagi — Human remains found near a fishing port have been confirmed through DNA testing to be that of sixth-grade student Koharu Hiratsuka, who had been missing since the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami of March 11, giving a measure of closure to her family.

The parents of 12-year-old Koharu — Shinichiro Hiratsuka, 45, and his wife Naomi, 37 — had been desperately hoping to locate at least part of their daughter’s body, and the confirmation brought both sadness and relief.

The remains were found near the fishing port in Naburi Bay by local fishermen, several kilometers from Okawa Elementary School in Ishinomaki, where Koharu was when the tsunami struck. Shinichiro and Naomi headed to Naburi to identify the body on Aug. 9, confident that they would know whether it was their daughter by looking at her navel. Upon arrival, however, they found that the body had suffered more damage than they’d expected.

They did, however, recognize the multiple layers of underwear on the body as their daughter’s; it had still been cold when the quake and tsunami hit. They took the body home with them the next night, and had it cremated on Aug. 11.

Relieved by the confirmation that the body was indeed his daughter’s, Shinichiro says, “We can hold a proper funeral and send her off to be with everyone else.” Meanwhile, Naomi vows: “I will continue doing what I can to find other missing children.”

Search efforts for missing students continue near Okawa Elementary School (far left background). The mounds of dirt indicate areas that have already been searched. (Mainichi)

Of the 108 students at Okawa Elementary, Koharu and 69 other students were killed, and four are still missing. The school was completely submerged immediately following the tsunami, preventing those searching for missing loved ones from getting close.

Once the water had subsided, Shinichiro and Naomi shoveled through the soil looking for Koharu, along with the parents of other missing children. After Shinichiro returned to work, Naomi attended a driving school and obtained a license to operate heavy machinery in late June. She went on to dig through the ground with other parents of missing children, using machinery rented from the Ishinomaki Municipal Government.

After the March disaster, Shinichiro and Naomi’s other children, son Toma, 6, who this spring started attending Okawa Elementary School, and 2-year-old daughter Sae, whose vocabulary has expanded since she started going to daycare, continued to thrive. The Hiratsukas could not revel in their surviving children’s growth, however, with their eldest still missing. The longer Koharu remained unaccounted for, the more it unsettled them. It was already nearing the Bon festival, a Buddhist tradition honoring the dead, when Koharu finally came home.

On Sept. 11, six months after the quake and tsunami, police search operations were scaled back, with the Metropolitan Police Department’s back-up squad pulling out completely. Wondering what would happen to the four children still missing from Okawa Elementary, Naomi bid farewell to the squad in tears. After they left, she got back to digging.

Naomi says that until her daughter was found, she had been worried that her family would never find Koharu, and that they would be left behind as others turned to the future. The support of the other parents who continued to help her efforts is what drives her now. On behalf of those families who are busy searching for their missing children, Naomi says, “There are still more places that need to be searched.” She plans to continue supporting the search until all of the remaining four children from Okawa Elementary are found.

Reiko-san called me recently. I wasn’t able to find my phone quickly enough to answer it, so I got a message in an elderly voice:

Hello, [She doesn’t answer. What should I do? Oh, leave a message?] This is Reiko, Tenku-san. How are you? Please call me.

I called her back right away. Yuji, a volunteer who has adopted her as his grandma, was with her and had helped her call. Reiko-san said that she misses me and wished I could visit her again. She said she’s doing fine in the temporary housing unit, but very grateful for visitors.

Reiko-san is a lovely 83-year-old woman I met through Yuji when I was volunteering in Ofunato City. She has a clear, beaming face and speaks in thick Iwate-ben, the local dialect. Reiko-san’s back is bent nearly in half with osteoporosis and she can’t walk without a cane. Her back is bent so severely that her internal organs are compressed and she has stomach troubles. When we visited, Reiko-san was sitting on her bed by the window. Unable to walk far, the window is her connection with the outside world. She sits there all day long, calling out to passersby. My volunteer group offered her “tapping touch,” then chatted with her for a while. I fell in love with her.

Most days in Iwate Prefecture I volunteered by offering “tapping touch,” a kind of light, energy massage, to tsunami refugees. Teams of three to five volunteers would go around to evacuation centers and temporary housing units offering “touch” for about 15 minutes per person, then we would sit quietly and listen to their stories.

I offered “touch” to women, men, the elderly and children. I heard sad and terrible stories to which I sat quietly and listened. When offering “touch,” I practiced tonglen, a Tibetan Buddhist compassion practice. People often cry during “touch” or when telling their stories. Until this trip to Japan, in fifteen years’ time I don’t think I’d ever seen a Japanese person cry. On this trip, every day, many times a day I saw people cry.

Before going to Japan this June, I was unsure of what my role might be while volunteering in Tohoku. In the States, I am training in a hospital to be certified as a chaplain. I have learned to discern what people need from me while keeping my own religious views and background out of the picture. In Japan, I found what people needed most from me was for me to be a Zen priest.

I took about 500 malas (prayer beads), known as juzu in Japan, with me to Japan. Before I left, I sent out a last-minute request, which was answered by several American temples and Buddhist organizations, some of whom mailed the malas directly to my teacher’s temple in Japan. I also used part of the funds I collected to buy more malas at a discounted price, and I found more at the dollar store in my teacher’s town.

Before going I wasn’t sure exactly what I would do with the malas. When working as a chaplain in the States, I am very sensitive about proselytization, avoiding it at all costs. Zen Buddhists don’t proselytize. Japan is a Buddhist country, though, and malas are used by all Buddhist sects. They are also popular as secular items. Another concern was that sometimes the refugee centers don’t like items to be given out unless there are enough for everyone, and 500 malas are in no way enough for hundreds of thousands of people.

I needn’t have worried. The leader of the “touch” group said it would be fine to offer the malas to people after we visited, so I distributed the malas among our volunteer group and we all went our separate ways.

The malas came with a story: they were donated by Western people for Japanese tsunami victims. Over time, I watched the story grow. Most of the malas were Tibetan-style wrist malas made of rosewood. I told one of the volunteers how, upon hearing about the tsunami, His Holiness the Dalai Lama asked Tibetan monks to chant the Heart Sutra 100,000 times. Before long the story some volunteers told was that the malas were handmade by Tibetan monks as they chanted the Heart Sutra 100,000 times for Japanese tsunami victims. This made me smile.

Our small group of about 10 volunteers gave out all of the malas in under three days. If we had had thousands of malas, it still would not have been enough. I cannot express how much people appreciated them. People cried. The people of Northern Japan are very devout Buddhists. They are accustomed to making offerings and chanting in front of the Buddha every day. The malas they lost had often belonged to their mother, or their grandmother. Of course, they also lost their home altars, Buddha statues, chant books, bells, incense, and family refuge plaques. They are missing these very much as they begin to set up home in temporary housing units.

Though I thought the people might appreciate the malas, the overwhelming emotional response surprised me. An added benefit was that they allowed a window to open for people to speak about spirituality. At three months after the disaster, the timing was right for this. One woman I remember in particular carefully folded her new malas into a tissue, then wrapped the tissue in a clean cloth before placing them on the highest place in her cardboard corner of the gymnasium. She spoke of how she’d wanted to go back into her home as the waters came to save her malas and Buddha statue, but did not. This decision saved her life. She told me of others who tried to do the same and died. This woman was elderly and unable to walk quickly. As she hurried to escape, she appealed to Kannon Bodhisattva (Kwan-Yin, Avalokitesvara) to help her, and that help came. Before I left, I offered a compassion chant invoking Kannon. I left her unable to speak, silently sobbing with tears of gratitude.

Reiko-san also received malas and she wore them as if they were diamonds. When the tsunami came, she was visiting her husband in the hospital. I’m not sure of his illness, but she said he doesn’t seem to know she’s there. The hospital is on higher ground, so she was saved. Reiko-san’s entire neighborhood and all her friends there were swept away. Her daughter lives in Sendai and is safe, but with her husband ill, Reiko-san has no one left nearby. Reiko-san is lonely and afraid.

One of the other “touch” volunteers told me that when Reiko-san first went to an emergency shelter, she wasn’t able to walk well enough to get food rations and blankets. Because she’d been away from her own neighborhood when the tsunami came, she didn’t know people in the shelter. Some of them laughed at her and made fun of her. She was isolated, cold, and hungry until one man took her under his wing and made sure she was cared for. Now, he and his wife live across from her in the temporary housing unit, and he still visits her regularly and looks out for her.

Yuji calls Reiko-san “Grandma,” and speaks to her as one would a grandmother, with familiar language. The two of them obviously love each other and the relationship is very touching. Yuji took us to visit Grandma several times. One time we were even featured on national television.

One day as I was offering “touch” to Reiko-san, she grabbed my hands and held them tightly. I was sitting on the floor and she on her bed. I looked into her beautiful face and her story poured out:

“What are you most afraid of right now?” I asked her.

I don’t know how I’m going to live. I’m old and I lost everything. We lived on my husband’s pension, but now he’s in the hospital and . . . How will I get food? I can’t go to the supermarket. I have no money. Where will I go? I don’t know anyone. I’ve never lived anywhere but here.

Tears poured down her face. I wanted to take her in my arms and hold her, but I reminded myself Japanese don’t hug, and sat silently, holding her hands tightly, allowing her the space to speak.

Yuji asked Grandma if she’d like for me to offer chants for her new home. Her eyes lit up. “Would you do that?” she implores.

Of course.

We gathered some rocks from outside and made a small pile on the table. Reiko-san gave me one of the new tea cups she’d received the previous day, which I filled with water for the water offering, and I had some incense in my bag that a friend from Kyushu had given me. There was no lighter, so I lit the incense on the gas range. There was no Buddha image, so I asked Reiko-san to picture one in her mind.

Then I offered the Heart Sutra in Japanese and a dedication for peace, within and without. We left Reiko-san sitting on her bed as the scent of incense filled her new home. As we drove away, she waved to us from her window, calling out “Thank you!”

Yuji told me on the phone the other day that many of Reiko-san’s new friends at the temporary housing unit would also like to have malas. Please contribute malas or donate money to buy more here.

Today is my friend Takashi Nishiyama’s 62nd birthday. On March 18th, three days after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, Nishiyama-san, posted this comment on his Facebook wall:

Today is my friend Takashi Nishiyama’s 62nd birthday. On March 18th, three days after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, Nishiyama-san, posted this comment on his Facebook wall:

I’m ready to go the disaster relief. But great wall is very difficult for government! I’m ready to go to the disaster assistance, but big wall of government is very hard. I am impatient but I’ll try.

The next news came on March 22:

Tomorrow I will depart from Saiki for the affected areas. I plan to volunteer in the field of relief supplies and carried. This time our members number is 2 with 2 cars.

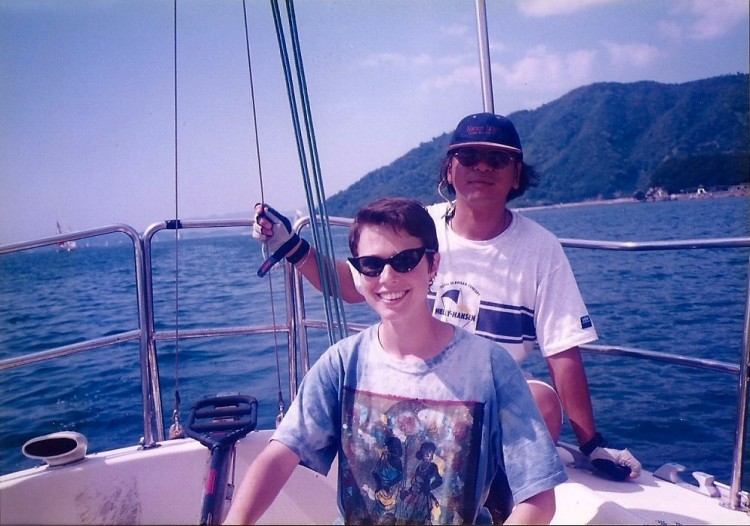

I met Nishiyama-san (his name means “West Mountain”) in August 1996, just after I arrived in Japan to teach English at Honan High School in Saiki City, Oita Prefecture (Southern Japan). I told a friend I was interested in sailing, and the next day I received a call from Nishiyama-san inviting me for coffee. Nishiyama-san is the president of the Saiki Sailing Club. That melting August afternoon, he and I sat in a cafe near the harbor and chatted in English about sailing. I didn’t speak Japanese at the time. At the close of the meeting, Nishiyama-san said, “Great! So, I’ll pick you up at 1:00 a.m. for the regatta.”

What!

Worried, I called the friend who introduced us. I didn’t know this guy at all, and

I was brand new to the country. My friend assured me that Nishiyama-san was a good guy so, with some trepidation, I entered the regatta with the team. We sailed all night to Uwajima, on Shikoku, the next island over, had a great time, and a strong friendship was born. Nishiyama-san and I continued sailing together for the three years I lived in Saiki and we have remained friends ever since.

Nishiyama-san is one of the most “good” people I know. He has a huge heart and his deepest wish is to help people. He can’t stand the thought that someone may not like him, and he endeavors to like everybody. He collects children who need a bit of extra care and teaches them to sail. He volunteers in various organizations, and when asked to help, he always says yes. Nishiyama-san is no saint in outer form–he’s just a regular guy, quick to laugh and joke that his boat runs on beer. His health isn’t so good, but he doesn’t let it prevent him from living his life to the fullest. He brings to mind the Buddhist exhortation to “burn yourself up, leaving no trace.”

Scaling the Great Wall

Immediately after the tsunami, many Japanese people wanted to go north to help, but the government told them to wait. First-response teams were combing the rubble for survivors (and bodies), there was no infrastructure, and the areas were dark at night and considered dangerous.

Nishiyama-san went to Saiki City Hall and asked how Saiki was going to help. City Hall said there was nothing they could do. Frustrated, he enlisted the help of Uesuki, one of the former sailing children (now an adult), and the two of them pulled the “Parates of the Saikiwan” (wan = bay) flag off the yacht, hopped in a small, borrowed truck and drove 900 miles north to Ishinomaki City, paying their own tolls, gas, and expenses. There were gas and food shortages at the time, so prices were inflated.

In Ishinomaki, Nishiyama-san and Uesuki first slept in the truck and then in a tent (Saikiwan flag flying overhead), living on Calorie Mate power bars and vitamin gel. It was bitterly cold and snow covered the ground. Still, in the chaos of the recent disaster, they found a way to help, using the truck to make food deliveries to people outside of official evacuation shelters. Nishiyama-san listened to people’s stories of floating on rooftops, watching their child being pulled away just out of arm’s reach, and climbing the one tree that was left standing. The children’s stories saddened him most deeply.

Facebook posting, April 2:

The affected areas are slowly changing. Enough rubble has been removed for some roads to become passable, but goods still haven’t reached everywhere. Yesterday, I heard there are plenty of local volunteers and supplies here, so the government will stop collecting donated goods. No way!! There isn’t nearly enough help or relief supplies! Why does the government spread such information? I’m looking for volunteers.

On April 18, after a month of hard work, Nishiyama-san pulled himself away from Ishinomaki with some difficulty and drove back to Saiki. As he left the disaster zone, he wondered what kind of dream he’d been in. Stopping at a hotel, after the proprietor bought him a beer and thanked him for doing what so many people wanted to do, Nishiyama-san fell asleep in the bathtub that night, exhausted. Back in Saiki, he couldn’t quite discern whether his month volunteering had really happened or not. Many volunteers, relief workers and tsunami survivors express this same sentiment. In one of the videos of the tsunami arriving at Ishinomaki, we can hear a woman alternately crying out loudly, and then stopping and asking, “Is this a dream? Is this a dream?”

Nishiyama-san returned to Saiki a hero. People were eager for stories, photos and firsthand information. He raised money, gave talks, and, over time, recruited over 100 volunteers from Saiki. He has become a point person for volunteers from other countries as well, offering his tent for their use and helping them figure out how to help. The Saiki City Hall was now eager to help, and Saiki sent its fire brigade to Ishinomaki. Saiki offered free housing to refugees. Local fishermen, upon hearing how much the devastated fishing communities craved fresh fish, sent an entire catch north. Saiki also donated a truckload of their local specialty, sesame soup stock, and the nearby city of Beppu sent a boatload of hot-spring water. On the June day that Fukan-san and I volunteered with Nishiyama-san in Ayukawahama he was awaiting delivery of a fishing boat, donated by Saiki fishermen so that fishermen in the devastated village could resume their livelihood.

May 21:

I am going back to Ishinomaki again to do volunteer work! My condition is very good for beer!!!!!

Currently, Nishiyama-san is on his fourth trip to Ishinomaki. When volunteers answer “Oita Prefecture” to inquiries about where they’re from, the locals say, “Oh, Saiki City?” I am so proud of Nishiyama-san, and of my Japanese hometown of Saiki. Nishiyama-san’s bravery in finding a way over the great wall of government has made way for hundreds of people to do something with the compassion they feel for Northern Japan. He is my hero. Happy birthday Nishiyama-san!

August 23:

My birthday today! Where was I going till now?

(Photos from various sources)

Okawa Elementary School is a name known to nearly everyone in Japan. When the tsunami warning came, the teachers weren’t sure how best to evacuate the students. No one thought the tsunami would come 4 kilometers upriver. There was snow and the mountain behind the school was very steep. Of the 108 students, 74 died and three remain missing. Ten of the school’s 13 teachers died. Some of the children who made it to the mountain wrapped their arms around trees; some were able to hang on and some were not.

Okawa Elementary School is about five minutes’ drive from Fukan’s temple, and six of the children who died were from Sho-un-ji. On the way back from looking through the rubble of Kannonji, we stopped at the school and offered the Daihishin Darani (Heart of Great Compassion chant) at a makeshift shrine in front of the remains of the school. The shrine had toys, stuffed animals, children’s cups, and messages to the lost children along with the usual flowers, water offerings, and funerary plaques. Chanting in front of it was one of the most difficult things I have done as a priest.

After we chanted, Fukan asked if I had read the messages. I had not, so she read one to me. It was from a mother to her daughter, Eri-chan. The message told Eri how sorry the mother was that she had not been able to protect her. The mother was sorry that Eri would never grow up, get married, and have children of her own. She said how much Eri’s older brother and the rest of the family missed her.

Hearing this message and standing in front of the destroyed school in the middle of a destroyed town after weeks of volunteering and listening to sad story after sad story, I started to cry. It was so unbearably sad.

When I first arrived at Sho-un-ji, Fukan’s teacher told me about one of the mothers of an Okawa Elementary School student. Her child was twelve years old and her body has not yet been found. The mother was heavily pregnant when the tsunami came. Soon afterwards her baby was born and then, not long after the birth, she took classes and became licensed to use heavy machinery. Now, on weekends when the machinery is not being used, the mother rents it to search on her own. Though her family begs her not to go, she goes anyway.

When Fukan and I were in the area, I looked for the mother out of the corner of my eye. I pictured her driving a large yellow power shovel, her face strong and determined. Her story makes me think of the Buddhist story of Kisa Gotami and her dead child, the Tibetan Buddhist teachings to regard all sentient beings as having been our mothers, and the phrase from the Metta Sutra:

Even as a mother protects with her life

Her child, her only child,

So with a boundless heart

Should one cherish all living beings

If you know of similar teachings from other religions, please post them in the comments section below.

More of my photos.

News stories about Okawa Elementary School

“Japan: Amid many tragedies, one school’s story,” GlobalPost, Gavin Blair March 25, 2011.

“At that Moment, What Should We Have Done… ” Pacific Friends Fund Blog. Takashi Sasaki. April 29, 2011

The following video is in Japanese, but you can get a good idea of the town and school’s story visually. It shows before and after footage, and the path of the tsunami. This is the area where Fukan lives. Her temple is along the road behind the next mountain finger beyond the school. The man’s voice you hear while watching the video of the tsunami coming in is saying, “Is the school o.k.?’

July 3, 2011. Fukan and I got up early in the morning, sat zazen (meditation), then did morning service. My sitting position during service directly faced the rows of memorial placards lining the back of the hall. (The left wall was lined as well.) I felt so awed and so grateful and so sad to offer chants for the boxes, photos and placards representing so many lost lives. Fukan asked me to chant the dedication and, as happened to her at the funeral, I did not know my voice would work until it came out.

After service, we had breakfast, drank coffee, called a mutual friend in the States, and then went out. First, we offered the Daihishin Darani (Great Compassionate Heart chant) at the ruins of Kannonji Temple’s graveyard.  All the stones were turned over and broken, and many of the graves lay open. The unbroken stones had been gathered into one area, which is where we offered the chant. A pair of black men’s shoes, a child’s toy, pink plastic flowers, and a woman’s purse (the contents neatly spread out on a wall), lay among the broken stones.

All the stones were turned over and broken, and many of the graves lay open. The unbroken stones had been gathered into one area, which is where we offered the chant. A pair of black men’s shoes, a child’s toy, pink plastic flowers, and a woman’s purse (the contents neatly spread out on a wall), lay among the broken stones.

Next, we drove about five to ten minutes along a rustic dirt road through what had once been a village but was now a flood plane, to Ryuukoku-in, the next temple over. The skeleton of a temple building, a shed, and the second floor of what had once been a two-story house remained.  Fukan told me that the elderly Abbot and his wife ran to the second floor of their house, just behind the main temple building, as the waters rose. The waters lifted the house like a boat. As it floated, it moved close to, then away from, close to, then away from the foot of the mountain. When it floated towards the mountain once more they both jumped from the veranda, swam a bit, and made it to safety. It was freezing cold and snow started to fall soon after. The wife was injured, but apparently they’re both o.k. now. They live with a relative in Sendai. Since the tsunami, the Abbot has been very busy with ceremonies, and hasn’t been able to come to the area more than once or twice. (The makeshift road to this area had just opened the previous week.)

Fukan told me that the elderly Abbot and his wife ran to the second floor of their house, just behind the main temple building, as the waters rose. The waters lifted the house like a boat. As it floated, it moved close to, then away from, close to, then away from the foot of the mountain. When it floated towards the mountain once more they both jumped from the veranda, swam a bit, and made it to safety. It was freezing cold and snow started to fall soon after. The wife was injured, but apparently they’re both o.k. now. They live with a relative in Sendai. Since the tsunami, the Abbot has been very busy with ceremonies, and hasn’t been able to come to the area more than once or twice. (The makeshift road to this area had just opened the previous week.)

Behind the temple, I saw zafus (meditation cushions), priest robes, sutra books, ceremonial items, incense boxes, juzu prayer beads, and more in the muck. I found this very disturbing, as did Fukan, and also my teacher when I told him later. I think it must be so for any priest, including the Ryuukoku-an’s Abbot. I couldn’t stand to leave the things lying there in the mud interspersed with animal and bird carcasses, but Fukan told me strongly to leave them just as they were, so I moved the two juzu and two small robes I’d already picked up to a dry place and left the rest. Fukan told me that Ryuukoku-in had earthquake insurance and will rebuild. I wondered what they will build and why they will rebuild in the same place. Interestingly, the temple graveyard fared much better than Kannonji’s, and on our way out we saw families cleaning up their plots.

Next, we donned gloves, boots, protective clothing and masks, and visited the remains of Kannonji, the temple nearest to Fukan’s temple. It had been completely destroyed and the temple’s members have now been absorbed into Sho-un-ji. Heavy machinery had already been there, so the rubble had been roughly sorted. We searched for 1) the temple’s main Buddha statue, 2) the temple records book, and 3) (this was unsaid) corpses. We found none. We collected some family photos, a wooden Kannon statue, a few more statues, and a bag full of o-ihai (funerary plaques). We put them into large plastic bags, loaded the car, and left.

Near Kannonji, we met Abe-sensei. He used to teach at Ogawa Elementary School and loved the area and the children, but was transferred to another school two years ago. Fukan greeted him familiarly. Apparently, Abe-sensei returns to the area any time he has a day or some time off from school to search among the ruins. He stops by Sho-un-ji on his way home. Though I suspected the answer, I asked Fukan what he searches for. Bodies. Many of the children from the school were never found.

July 2, 2011. Fukan-san and I volunteered in the tiny fishing village of Ayukawahama with Nishiyama-san, a close friend of mine from Oita Prefecture. Volunteers hosted a summer festival for tsunami survivors, and dancers came from Osaka, Sendai, Tokyo, and Kyoto to perform their region’s traditional summer dances. Vendors from the various regions came as well, offering traditional festival foods like yakisoba noodles, takoyaki (grilled octopus dumplings), neon-colored shaved ice, and yakitori (grilled chicken). No money exchanged hands. Children played games in the water. It was a very strange setting, with brightly clothed, smiling, energetic young people dancing amidst a backdrop of pure ruin. The evacuees seemed to enjoy themselves, though, especially children and the elderly. One elderly woman learned the dances well enough to join in towards the end.

July 2, 2011. Fukan-san and I volunteered in the tiny fishing village of Ayukawahama with Nishiyama-san, a close friend of mine from Oita Prefecture. Volunteers hosted a summer festival for tsunami survivors, and dancers came from Osaka, Sendai, Tokyo, and Kyoto to perform their region’s traditional summer dances. Vendors from the various regions came as well, offering traditional festival foods like yakisoba noodles, takoyaki (grilled octopus dumplings), neon-colored shaved ice, and yakitori (grilled chicken). No money exchanged hands. Children played games in the water. It was a very strange setting, with brightly clothed, smiling, energetic young people dancing amidst a backdrop of pure ruin. The evacuees seemed to enjoy themselves, though, especially children and the elderly. One elderly woman learned the dances well enough to join in towards the end.

Personally, I couldn’t get into it. Fukan and I had the job of standing on the roadside and directing traffic towards parking lots. There was almost no traffic, so I did a lot of standing in the sun, sweating, and chanting the Heart Sutra.

I became absorbed by the ruins of the house next to me. It was apparent that no one had been there since the tsunami. This was true for much of the town, though we saw a few people sifting through debris. What makes up th e ruins of a life? A Swiss Army knife, open, with a name written in marker, lay on a wall. A TV perched on the roof next to a laundry basket. As first, looking into the debris, all one sees is a pile of rubble. Then the eye adjusts and you see a tiny prajñā [wisdom] character printed on a tiny shard of tea cup. (The cup must have had the Heart Sutra written on it. It probably came from the altar. I guess.) Then, a cutting board sticking out of a pile of rocks right in front of my eyes. Potato, tomato, kabocha pumpkin, and dokudani (a weed that can be used for medicine) plants grow in a pile of rubble in what must have been the courtyard. A navy blue sweatshirt hangs from one arm on a nail in an open window (that bothered me the most). One geta sandal. One spoon. A lace blouse pushed solidly under the lamppost I’d been standing by all day showed itself only after lunch. A lacquer bowl. A small stuffed elephant. A tiny gold plastic flower.

e ruins of a life? A Swiss Army knife, open, with a name written in marker, lay on a wall. A TV perched on the roof next to a laundry basket. As first, looking into the debris, all one sees is a pile of rubble. Then the eye adjusts and you see a tiny prajñā [wisdom] character printed on a tiny shard of tea cup. (The cup must have had the Heart Sutra written on it. It probably came from the altar. I guess.) Then, a cutting board sticking out of a pile of rocks right in front of my eyes. Potato, tomato, kabocha pumpkin, and dokudani (a weed that can be used for medicine) plants grow in a pile of rubble in what must have been the courtyard. A navy blue sweatshirt hangs from one arm on a nail in an open window (that bothered me the most). One geta sandal. One spoon. A lace blouse pushed solidly under the lamppost I’d been standing by all day showed itself only after lunch. A lacquer bowl. A small stuffed elephant. A tiny gold plastic flower.

After lunch, Fukan and I poked around the remains of the community center. It now serves as a distribution center, with neatly arranged used clothing (mostly winter things) in one room, and cleaned-up-important-items recovered from houses in another (photos, prayer beads, statues, Japanese dolls, keys).  There is a playroom for children, a storage area, a food distribution area, an area for some sort of paperwork, and a back room where the volunteers sleep. Fukan checked to see that no one was around (it feels odd to take photos in such places), then took a photo of the water line, high up on the wall of the community center theater space. The line was even and smooth, not far from the ceiling. The clean, straight, brown line seemed strange to me among so much disorder.

There is a playroom for children, a storage area, a food distribution area, an area for some sort of paperwork, and a back room where the volunteers sleep. Fukan checked to see that no one was around (it feels odd to take photos in such places), then took a photo of the water line, high up on the wall of the community center theater space. The line was even and smooth, not far from the ceiling. The clean, straight, brown line seemed strange to me among so much disorder.

We went on a short walk through town and unconsciously ended where the tsunami did, slightly uphill. Seeing repairs taking place on one of the less-damaged houses, I asked why people would rebuild in such a place. Fukan said that the owners probably had earthquake insurance and rebuilding is the most affordable option. After all, the land is still theirs, the house still has a foundation and some structure, and besides, where else would they go?

Fukan talked to me in the car the whole way back–about an hour and a half. She said she’s glad she went because now she knows that doing that sort of thing is more than she can handle. She realized on this day that her work in the temple is where she can do the most good, with people coming for tea every day, all day long. She officiates at funerals, and, soon, memorial services as well. She tells me before today she felt like she should somehow be doing more, like volunteering, but now she understands her role better. I feel I am watching her mature as a priest before my eyes, and wonder what this experience will teach me.

Fukan wants to go to Kannonji, the next temple over from hers, the next day to sort through the rubble. She asked if I might help with that. It’s been too much for her to think of doing alone, and she’s only gone to that area–five minutes away from her temple–once since the tsunami. The Abbot is elderly and very kind-hearted. She says taking charge of such a task is too much for him. Over 90 members of his temple died, the entire temple was destroyed, and many people remain missing. He can’t face it. He is living with a son in Sendai now, and has no way back even if he wanted to come.

After we returned to the volunteer base camp in Ishinomaki City, we said goodbye to Nishiyama-san, had a lovely meal of soba, and came back to the temple. What a relief. Fukan lives in a cleared out a storage room next to the main temple building. It’s quite comfortable and very quiet. Each night, as we lay in our futons, though we were both exhausted, we talked for a while. Though she says she is over her limit, Fukan keeps going, constantly stretching her previously defined limits. I am so impressed.

More photos

More photos

Though I visited Fukan-san toward the end of my trip, I want to write about her now. Fukan is a friend from my training days at the Aichi Senmon Nisodo (Women’s Monastery) in Nagoya City. She is not what I thought of as a “nun’s nun,” but rather, a breath of fresh air in an environment that emphasizes similarity. Her robes are never quite straight, her posture is a bit slumpy, and Fukan prefers a joke, delivered in deadpan, to austere silence. I fondly remember her raucous laughter echoing through the silent hallways after lights-out. Though at first Fukan wasn’t too keen on training at the Nisodo, she gradually shifted, coming to appreciate zazen (meditation), Abbess Aoyama Roshi and her teachings, and the lifestyle offered there.

Though I visited Fukan-san toward the end of my trip, I want to write about her now. Fukan is a friend from my training days at the Aichi Senmon Nisodo (Women’s Monastery) in Nagoya City. She is not what I thought of as a “nun’s nun,” but rather, a breath of fresh air in an environment that emphasizes similarity. Her robes are never quite straight, her posture is a bit slumpy, and Fukan prefers a joke, delivered in deadpan, to austere silence. I fondly remember her raucous laughter echoing through the silent hallways after lights-out. Though at first Fukan wasn’t too keen on training at the Nisodo, she gradually shifted, coming to appreciate zazen (meditation), Abbess Aoyama Roshi and her teachings, and the lifestyle offered there.

Fukan had just completed five years of training at the Nisodo when the earthquake and tsunami struck. In fact, her completion ceremony took place on March 13, two days later. After the disaster, there was no electricity, gas, telephone access, or running water at Sho-un-ji, Fukan’s home temple in Ishinomaki, nor was there any entrance or exit by road or sea. You can look at this map to get a sense of the landscape. Because the temple is located next to the Kitakami River, and not the ocean, no one expected the tsunami to strike there. As such, Fukan had no idea how badly the area had been hit until she made it there in person many days later. I heard Sho-un-ji’s story from Fukan’s shisho, or Zen master/teacher, an 80-year-old monk.

Sho-un-ji.

July 1, 2011. It was cold the afternoon the earthquake and tsunami came. Yaguchi Roshi, Fukan’s shisho, was at home with his wife.They felt the earthquake hit and then heard the general alarm announcing a tsunami. Like others in the neighborhood, though, they did not expect a tsunami to come up the river. In fact, many people in the area died because they were standing on the river wall or the stoops of their homes, watching it come in.

Yaguchi Roshi did not know what was going on when people started to show up at the temple. What was happening becomes more clear from the map. As the waters rose from the river, people fled upriver until the escape road also was flooded. The only place to go was into the mountains away from the river, which is why they came to Sho-un-ji. Members of the small, close-knit community began showing up on the steps of the one local temple that was not destroyed.

Almost as soon as the first people arrived in a panic, more came, and then more. It was bitterly cold, and soon snow began to fall. In almost no time at all between 70 and 80 people were huddled into every available space in the temple. Fortunately, the temple had just filled up their large kerosene tank, and they had five or six kerosene heaters to offer some warmth. Blankets were distributed and the temple’s stores of food offered. With no gas, people were not able to cook, but they made food on the heaters and over fires. Some used seawater to cook rice.

After the waters receded and dusk came, more wet and bedraggled survivors drifted in. Two elderly women in their 90’s were drenched to the bone and shivering violently. Yaguchi Roshi worried they would die, but after they received dry clothes, tea, and warmth, they slowly recovered.

Sho-un-ji is not a designated evacuation site, so the authorities did not know to look there for survivors. Some people ventured out, reporting back to the group on the horrors they encountered. When the police did not show up, people waded into the icy water to retrieve corpses themselves. The temple offered its land to bury them, and people from all different sects of Buddhism were interred on its grounds. Though the temple offered every bit of food and supplies it had, it only had about three days’ supply for so many people. People were forced to move to a formal evacuation shelter further away from their former homes.

Only after time, as the days blurred, did the story of the tsunami slowly reach the survivors. When electricity was restored and people could see or hear the news, they were shocked. Kannonji, the neighboring temple had been completely wiped out, as had the next one. The local elementary school, just around the corner from Sho-un-ji, was destroyed, killing 74 of the 108 students and 10 of the 13 teachers. Twenty-six of Sho-un-ji’s members have been confirmed dead; Kannonji lost at least 90. More than 20 people from the immediate area remain missing.

Not long after the tsunami hit, Yaguchi Roshi became gravely ill with pneumonia and had to be hospitalized in Sendai for two weeks. It was to this environment that Fukan, freshly minted as a full priest, returned. When I visited Sho-un-ji, a steady stream of visitors arrived throughout the day and into the evening for tea, coffee and chocolates sent from a Columbian nun and her community, and conversation. Fukan estimates that she and her teacher visit with about 30 people each day.

The first funeral at which Fukan was the officiant was for multiple people. Japanese people usually cremate the bodies of the deceased, but after the tsunami the crematoriums could not keep up, so people were buried in the ground. Most Japanese people have never seen coffins. As Fukan stood, surrounded by coffins and mourners, she felt her voice would not come to offer the chants. She told herself, “I think I can do one chant, but no more.”

The chant came. And then the next one, and the next. Then she thought, “ . . .but there’s no way I can offer the eko (dedication).” The eko came.

It is customary after a funeral service for the priest to offer a few words. In this situation, Fukan had no idea what to say, and only a few simple words about returning to the sea came out. She felt like a failure as a priest.

When I told this story to my teacher, he was deeply moved, remarking reverently, “That was the best priest training (shugyo) possible. Your friend is going to be a nun among nuns.”